Historic Central New York Characters

Elizabeth "Libba" Cotten

Elizabeth “Libba” Cotten was born in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, on January 5th, sometime in the early 1890s. The daughter of a miner and a housemaid, Cotten showed a deep prowess and passion for music. Even though she was forbidden from doing so, Cotten would sneak into her brother’s room and play his banjo while he was at work. After leaving school and taking some housekeeping jobs for white families, Cotten was able to save up for her own guitar from a local shop. From then on, she got to work teaching herself how to play.

Cotten had a unique way of playing her music. She found playing her guitar “upside down” made playing more comfortable, as she was left-handed. Cotten strummed with her left hand and held the frets with her right. She would also pick at the bass strings with her fingers and pluck the melody strings with her thumb. This method of playing would later become known as the “Cotten style.” By the time she was 14, Cotten was able to play a range of songs in different styles, including some of her own compositions. She would even stay up at night playing different songs until her parents told her to stop. This period of musical experimentation would not last, however.

Elizabeth would marry her husband, Frank Cotten, at the age of 15. Around the same time, Elizabeth would experience a religious conversion and became tenaciously devoted to the church. While she still played the guitar every now and then, the deacons of her new church opposed it. To them, she was playing “worldly” music that was “for the devil,” and she needed to stop. The boredom of playing religious songs, along with the chores she needed to do around the house, made Cotten put down the guitar for almost 50 years. Even though she put her passion for music aside for some time, it happily wouldn’t stay that way.

In 1943 Cotten moved to Washington, DC, to be closer to her daughter and grandchild. While working at a department store, Cotten would help a girl reunite with her mother, Ruth Crawford Seeger. As thanks, Seeger offered Cotten a job as a domestic servant, which Cotten accepted.Little did she know that Ruth and her husband Charles had backgrounds in musicology. When he heard Cotten play their daughter’s guitar, Charles started making recordings of her performances.Before she knew it, she was playing gigs in the homes of senators, including that of John F. Kennedy. 1958 saw the release of Cotten’s first album, Elizabeth Cotton: Negro Folk Songs and Tunes. The most notable song on the album was “Freight Train,” a song she wrote when she was twelve.Several notable acts have covered her songs, such as The Grateful Dead’s rendition of “Oh, Babe, It Ain’t No Lie,” or Bob Dylan’s versions of “Shake Sugartree” and “Freight Train.”

“Freight Train,” along with the album, became a hit in folk music circles all across the country. Tours and concert gigs soon followed, with Cotton performing right up to the end of her life. In 1983, Cotten bought the Syracuse house she would spend her time in when not on tour. She passed away in 1987.Despite her career starting late in life, Elizabeth “Libba” Cotten and her passion for music had a massive impact on folk music that can be felt to this day.

Syracuse named Libba Cotten a Living Treasure in 1983, two years before she received her first Grammy Award at the age of 90.She was declared a National Heritage Fellow by the National Endowment of the Arts and recognized by the Smithsonian Institution. In 2012, a bronze statue of the musician was erected in a park, renamed “Libba Cotten Grove”, at the corner of State and Castle Streets on the City of Syracuse’s South Side. Libba Cotten was posthumously inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2002,recognized as an Early Influence. Her Grammy Award, which is part of the Onondaga Historical Association’s collections, is on loan to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

Sources

●https://folkways.si.edu/elizabeth-cotten-master-american-folk/music/article/smithsonian

●https://www.arts.gov/honors/heritage/elizabeth-cotten

●https://www.grunge.com/1075665/who-was-elizabeth-cotten-the-self-taught-blues-and-folk-musician/

●https://www.npr.org/2022/06/29/1107090873/how-elizabeth-cottens-music-fueled-the-folk-revival

Gustav Stickley

Gustav Stickley was born in Osceola, Wisconsin on March 9, 1858.The eldest son of two first-generation German immigrants, Stickley would live his first years of life on his family’s farm while receiving a formal education.This would end in 1869 as a result of his parents separating and Stickley would leave formal education after sixth grade.At the age of 12, he decided to take up his father’s trade of masonry to help support his struggling family.His path to notoriety would begin only 6 years later when he moved to Brandt, Pennsylvania in order to work in his uncle’s factory.It would not take long for Stickley to rise through the ranks until he managed the factory.Gustav went on to form the Stickley Brothers Furniture Company with his brothers, Albert and Charles, in 1883.That same year, the company’s headquarters would move from Susquehanna, Pennsylvania to Binghamton, New York.The company itself would not last long, eventually dissolving and making Albert and Charles seek out new ventures.

Gustav would continue in the furniture industry. Founded in Syracuse’s Eastwood area, Gustav would go on to create The Gustav Stickley Company in 1898.His specific style of furniture was heavily influenced by Art Nouveau and England’s Arts and Crafts Movement.The latter was a particularly major influence.Stickley had taken trips to England in 1895 and 1896, becoming inspired by the Arts and Crafts Movement’s emphasis on quality, handcraft, and simplicity.He would use this inspiration—along with the help of designers Henry Wilkinson and LaMont A. Warner—to create his “New Furniture” line.This line was typified by simple designs and materials that emphasized each piece’s construction.Oak was colored in a way to draw out its grain and joinery, while iron handles were hammered in a way that showed their hand-crafted construction.This style would later become known as “mission” or “Craftsman” design.These pieces would be shown off in two places.First would be his display room, Syracuse’s famous Crouse stables., which would become so popular that the stables would later be renamed the Craftsman Building.The second place would be in his magazine.

In 1901 he launched The Craftsman with Irene Sargent, a professor of art history at Syracuse University and the magazine’s editor.The Craftsman grew to cover not just furniture design and home crafts, but also architecture, literature, music, city planning, and political issues.This served to be a useful tool to promote the Arts and Crafts movement’s philosophy, along with advertisements for Stickley furniture.

Though his work would be carried by hundreds of stores, Gustav Stickley’s success could not last forever.In 1913, one year before the outbreak of World War One, Stickley bought a 12-story headquarters building in midtown Manhattan.The company was losing money, interest in the Arts and Crafts movement was waning, and competition was on the rise.In 1915, Gustav filed for bankruptcy, owing nearly a quarter of a million dollars. Stickley eventually moved back to Syracuse with his wife, where she died of a stroke in 1919.Gustav would live with his daughter Barbra and her husband until he died on April 21, 1942.The company that bears his family’s name continues to be headquartered in Manlius.

SOURCES

●The Stickley Museum at Craftsman Farms:https://www.stickleymuseum.org/history/

●Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Gustav-Stickley

●New World Encyclopedia:https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Gustav_Stickley

Eric Carle

Eric Carle was born to German immigrants on Syracuse's North Side in 1929. His family returned to Germany six years later. Carle returned to the United States in 1952 and worked as a graphic designer for the New York Times. He is the beloved children's author and illustrator of books like "The Very Hungry Caterpillar" and "Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What Do You See?" He has credited his first grade teacher at U.S. Grant School (now Grant Middle School) with recognizing and supporting his creative talents.

Carle's books utilized bright bold colors and simple words to convey comfort, hope, and delight in the world around them. The designs were often developed using pieces of tissue paper. His books have been translated into more than 60 languages and have been a favorite of families, teachers, and pediatricians since the 1960s. He has written, illustrated, and co-written more than 75 books.His work has been turned into learning tools and has even inspired plays.

In 2014, Eric Carle released "Friends", a book about a childhood friend from his days in Syracuse. All he had to remember her by was a photo of the two of them hugging in front of his home on John Street. He didn't remember her name but did know that her family was Italian and that they would enjoy playing together when she came to visit her grandparents. Neither of the two children remained in Syracuse, but the memories of their friendship endured.

Upon releasing the book, which was designed around the photo from his scrapbook, Carle expressed his hope of finding his dear friend. The Syracuse Post-Standard assisted in tracking down the little girl, named Flo (Ciani) Trovato, and the two reunited after 83 years. Ironically, Trovato translates to "found" in Italian.

Eric Carle passed away in 2021.

Rev. Jermain Wesley Loguen and Sarah Loguen

Jermaine Loguen devoted most of his life to fighting slavery. He was born enslaved in Tennessee and escaped when he was around 20 in 1834. After a perilous journey north, Loguen reached Canada and freedom. He worked as a farmer in Ontario for three years before moving to Upstate New York. Loguen initially settled in Rochester but moved to Syracuse in 1841. While living in the city, he was ordained to preach in the African Methodist Episcopal Zion (AMEZ) Church. Although he continued to work as a pastor in the years to come, Loguen quickly became much better known for his work on the Underground Railroad. The Loguen household grew to be the main safehouse in Syracuse, and the family did not try to hide their ties to the abolitionist movement. Loguen wrote about his work to Syracuse newspapers in an effort to further the cause and published an autobiography recounting his experiences in 1859. The home is now gone from its original location near the corner of Pine and East Genesee Streets in Syracuse’s Near-Eastside neighborhood.A closed Walgreens Pharmacy now occupies the corner.Today the Loguen’s home is noted on a marker for the Freedom Trail, reminding the community and visitors of the important role the Loguen family played in the Abolition Movement.

Over the two decades after he arrived in Syracuse, Loguen is estimated to have aided upwards of 1,500 escaping slaves. Perhaps the best known such instance was the rescue of William “Jerry” Henry on October 1, 1851. Jerry, who had been arrested under the unpopular Fugitive Slave Act, was broken out of the Syracuse jail by a crowd of thousands and safely taken to Canada.Loguen himself briefly had to spend time in Canada as a result of his involvement in the rescue – which was nominally illegal. For his work helping free enslaved people, Loguen became known as the “King of the Underground Railroad.”

After the end of the Civil War, Loguen did not cease his advocacy for African-Americans and became a bishop in the AMEZ church. He died on September 20, 1872, and was buried in Oakwood Cemetery.

One of Jermaine Loguen’s children, Sarah Loguen Fraser, was also a pioneer, but in the medical field. She was born in Syracuse on January 29, 1850, the fifth child of a family that would eventually include eight. Shortly after her father’s death, Sarah entered the Syracuse University College of Medicine. She graduated in 1876, becoming the fourth known African-American woman to become a doctor.

Alfred Jacques

Alfred “Alf” Jacques was one of the greatest ambassadors of any sport. The sport? Lacrosse. His primary contribution? Making by hand wooden lacrosse sticks. He would craft over 80,000 in his life.

Born to a Mohawk father, from the Akwesasne territory, and an Onondaga mother, Alf spent his entire life on the Onondaga Nation. He was taught the traditional way to handcraft lacrosse sticks by his father, Lou. He also credited his grandmother for instilling in him pride and precision in his work by teaching him how to make baskets at a young age.Father and son decided to craft their own lacrosse stick when they didn’t have the money to buy one. Through trial and error, they fashioned a method that Alf would use for the rest of his life.

It became a business. By the 1970s, the Jacques were crafting about 12,000 sticks a year.That number would fall as plastic sticks would become the standard, but he would continue the craft until he died. Many Jacques sticks have become collector’s items. Some were still used in competition well into this century.

Over the years he became a legend in lacrosse. Division One college programs have made pilgrimages to his workshop. Many players and coaches, legends themselves, have Jacques sticks in their collections.Football coach Bill Belichick, a former lacrosse player and huge supporter of the game, had a wooden stick he owned repaired by Jacques.

His passion for his craft is tied directly to his passion for the game itself, as he didn’t just make sticks, but used them as well, playing and coaching in many leagues. Jacques also advocated for its central position in Onondaga culture. “It’s such a part of who we are as a people,” he said. “It is important, as it allows us to play the Medicine Game the way it should be, with all wooden sticks.” Says Oren Lyons, Onondaga Nation Faithkeeper, “The stick, two goals, no referees, no coaches. Just the men, the ball, the stick, and the spiritual purpose for the welfare of people and the welfare of the earth. It’s never been a sport with us. That’s why we still play it.” “I learned a great deal from him,” says Mike Messere, longtime head coach of the West Genesee High School lacrosse team, “I had a great relationship with him through the years. He passed on the word. He let people and kids go out and play a sport. It’s such a great game that’s so important. It’s become part of our history.”

Alf Jacques died in 2023. “He didn’t have any regrets,” said his son Ryder. “He did everything he wanted to do.”

Source material: Syracuse Post-Standard.

Karen DeCrow

Karen DeCrow was one of the most prominent women’s rights activists in the United States. She first became active in the women’s movement after graduation from Northwestern University, where she studied journalism. DeCrow, who was born and grew up in Chicago, followed her second husband to Syracuse but remained there even after their divorce. She gave up her dreams of a lifelong career in journalism after realizing the field suffered from serious gender inequality, in both pay and opportunities.

After arriving in the city she founded a Syracuse chapter of the National Organization for Women (NOW), an organization that advocated for equality of treatment and opportunity. She attended and graduated from the Syracuse University Law School. She was the only woman in her class. She began working in gender-related litigation while continuing her work with NOW. She was soon named to the national board of directors, on which she served from 1968 to 1974. During this term, she was a coordinator for the Women’s Strike for Equality in 1970. Afterward, she was named president of the organization, a role she held from 1974 to 1977. Through NOW, DeCrow was highly involved in working towards gender equality in education and sports, heavily advocated for the adoption of the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), and she protested against violence toward women. She held a “Take Back the Night” march, fought efforts to limit Title IX, visited the White House (NOW’s first president to do so), and traveled around the world giving speeches and touring countries. During her advocacy for the ERA, DeCrow regularly came into conflict with Phyllis Schlafly, a prominent member of the STOP ERA movement. The two debated the amendment over 80 times.

DeCrow published several books on gender equality, including The Young Woman’s Guide to Liberation; Corporate Wives, Corporate Casualties; Women Who Marry Houses; and Sexist Justice; wrote articles in national publications; and wrote columns in Syracuse newspapers. She ran for mayor of Syracuse in 1969 (while still in law school), the first woman to do so in a major New York city. After graduating, DeCrow became known for her work in cases fighting for gender equality, for men and women. She drew national attention for her lawsuits over entry to male-only bars.

DeCrow received a number of awards during her life. As president of NOW, Time named DeCrow one of America’s 200 Future Leaders. In 1985, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) awarded her the Ralph E. Kharas Award. In 2009, she was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame, largely for her work with NOW. She died on June 6, 2014, of melanoma.

After her death, DeCrow has been remembered as a trailblazer in the field of women’s rights and gender equality. Stephanie Miner and others have cited her work as allowing them to have greater career successes. The Syracuse Post-Standard quoted Miner upon DeCrow’s death as saying "Never did Karen think why something couldn't be done. She stood up and was the change she sought to bring to our community. Her perseverance, dedication, and strong work ethic made a major difference in our community and across the country."

Lyman Frank Baum

Lyman Frank Baum, born on May 15, 1856, in Chittenango, New York to parents Benjamin and Cynthia Baum. is of course best known for his children’s fantasy books, most notably The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. He was the seventh of nine children and married Maud Gage on November 9, 1882.She was the daughter of the daughter of Matilda Joslyn Gage who was known for her contributions to women’s suffrage, campaigning for Native American rights, abolitionism, and freethought.

Baum’s inspiration came from his fascination with flight, like several of his peers, and it is possible that he was inspired by hot air balloon ascensions that happened in Central New York in 1870 and 1871.During this time, Baum was living with his father after spending two years at Peekskill Military Academy and having been sent home. He started writing as soon as he returned home and, in the fall of 1870, worked with his brother, Henry, to start their own news magazine, which they were able to print themselves. The brothers could do this because their father’s wealth allowed them to buy their own printing press. In 1888, Baum and his wife moved their family to Aberdeen, South Dakota (then Dakota Territory) where they opened a store called “Baum’s Bazaar” which went bankrupt because of Baum giving out items on credit.

He started a job editing the local newspaper The Aberdeen Saturday Pioneer where he wrote the column Our Landlady. The newspaper failed in 1891 and Baum moved his family to the Humboldt Park section of Chicago where Baum found a job as a reporter for the Evening Post. In 1897, he founded a magazine called The Show Window, later called Merchants Record and Show Window, which focused on store window displays, retail strategy, and visual merchandising. In 1897, Baum published Mother Goose in Prose, a collection of rhymes written as stories and illustrated by Maxfield Parrish. The success of the book allowed Baum to quit his sales job. Baum partnered with W. W. Denslow in 1899 to publish Father Goose, His Book, a book of nonsense poetry; it became the best-selling children’s book of the year. When Baum and Denslow published The Wonderful Wizard of Oz in 1900, it was the best-selling children’s book for two straight years.

Baum continued the series and eventually wrote thirteen books based on the places and people in the Land of Oz. After the book was published Baum and Denslow worked with composer Paul Tietjens and director Julian Mitchell to produce a musical of the book, but it was rejected. This musical eventually opened in Chicago in 1902 and ran through 1904.The show toured the United States with much of the same cast until 1911 when it became available for amateur use. Baum wrote over 60 other books using various pseudonyms. In 1914, Baum started a film production company called The Oz Film Manufacturing Company and was the president, principal producer, and screenwriter. The company would fail because, ironically, the name Oz had become box office poison. aum died on May 5, 1919, after suffering a stroke. His last book, Glinda of Oz, was published posthumously in 1920.

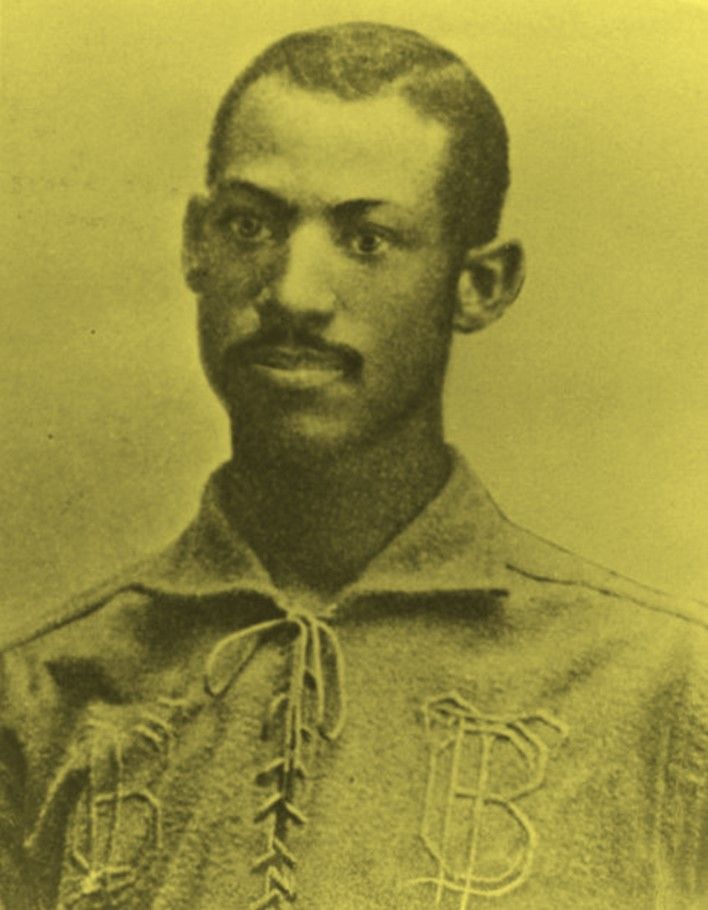

Moses Fleetwood Walker

Moses Fleetwood Walker was born on October 7, 1856, in Mount Pleasant, Ohio to Moses W. Walker and Caroline O’Harra. Mount Pleasant had been a sanctuary for runaway slaves since 1815 and it had a large Quaker community. Both of Walker’s parents were mixed-race and his father came to Ohio from Pennsylvania and was likely a beneficiary of Quaker patronage. Three years after Walker was born, his family moved to Steubenville where his father became one of the first black physicians in Ohio. Walker attended Oberlin College in 1878 where he majored in philosophy and the arts. He was an excellent student but for reasons unknown, he was barely attending classes by his sophomore year .Baseball, a popular game for Steubenville children, was probably a factor.

During his time at Oberlin’s preparatory program, Walker became the catcher and leadoff hitter for the college’s team. Baseball was being played as early as 1865 through organized club matches and there was a black first baseman before Walker joined which meant that Walker was not the first black college baseball player. Oberlin lifted their ban on off-campus competition in 1881 and Walker was able to play on the baseball club’s first inter-collegiate team along with his brother Weldy. His performance on the team led to the University of Michigan recruiting him to their program. Transfers at the time were generally informal and recruiting from other teams was hardly unusual. Walker accepted the transfer and was accompanied by his girlfriend Arabella Taylor who was pregnant at the time, and they married a year later.

Walker was signed to the Toledo Blue Stockings in 1883 and the next year the team joined the American Association. a major league that formed in 1882 as a rival to the National League. With this development, Walker became the first black player in Major League history closely followed by his brother Weldy, who joined later in the year. As a result of financial problems, the Toledo club shut down which put an end to the Major League careers of both Walker and Weldy. They would be the last black players in the majors until Jackie Robinson joined the Dodgers in 1947.Walker was eventually brought to the Syracuse Stars by Charlie Hackett, who had been hired as the manager when Joe Simmons chose not to return. There had been racially fueled tensions between the team’s pitcher, Robert Higgins, and other members of the team and Hackett chose to bring in Walker as catcher with the idea that Higgins would be more comfortable pitching to a black catcher. This ended up being a great idea as the team went on to win the International League championship in 1888.

By the next season, however, Higgins had tired of the racial unrest and left the team midseason while Walker finished the season and then left as well. All black players were banned from organized baseball the next season. Walker’s wife, Arabella, died on June 12, 1895, from cancer and he remarried three years later to Ednah Mason. When Ednah died in 1920, Walker chose to move to Cleveland with Weldy where he lived until he died in 1924 of lobar pneumonia. He was buried at Union Cemetery-Beatty Park next to his first wife.

Henry Keck

Henry Keck was born in Geissen, Germany in 1873.He was first introduced to craftsmanship by his father, a woodworker and cabinetmaker. Henry Keck Sr. had moved his wife and seven children over to America during the economic turmoil of the 1880s.When Keck was seven, he started an apprenticeship at the stained-glass workshops of Louis Comfort Tiffany, an interior designer of Art Nouveau fame who was known for his pioneering innovations in glass design. Along with learning glass cutting and glazing from Tiffany, Keck decided to go further with his education and learn the art of stained-glass design.

While in New York City, Keck took night classes at the Art Students League, and in 1895 he went back to Germany to study glass design and glass painting for two years at the Royal Academy School of Industrial Art in Munich. When Keck came back to the United States, he found that designer jobs were few and far between but did find a job at a glass studio in Chicago. He eventually returned to New York and became a designer and glass painter for Montague Castle Studios. Keck married Myra Graff in 1903 and they had four children together. He joined the Pike Stained Glass Studio in Rochester as a designer in 1909.Keck would tire of working for other people and in 1913 he opened his own art glass studio in Syracuse where there was no competition. It is likely that Keck chose Syracuse because of his acquaintance with architect Ward Wellington Ward. Ward had commissioned glass from the Pike studio while Keck worked there.

After 1913, Ward only used glass made by Keck in his Syracuse houses. One such project was eighteen windows for a house Ward designed for Dr. Harry Webb, which are important examples of American art glass. While Keck had many commissions from Ward, he also did a lot of other work, such as the design and fabrication of church windows. Keck’s windows have a distinctive style that is simple and inventive. He used thick outlines to emphasize natural figures and mosaic-like patterns. His use of opalescent glass for its bright, pure colors and unique textures created amazing moods of changing light.

By 1920, there were about 900 glass studios operating in America and Keck had a reputation as one of the best in the business. The bulk of his reputation came from the Gothic revival windows he would design for churches. Henry Keck died in 1956 but his studio remained open thanks to his apprentice and longtime associate Stanley Worden, and the Henry Keck Studios continued to make glass windows until the studio closed in 1974. It is largely because of Worden’s stewardship that Henry Keck continues to hold such an esteemed place in the world of stained glass artistry.

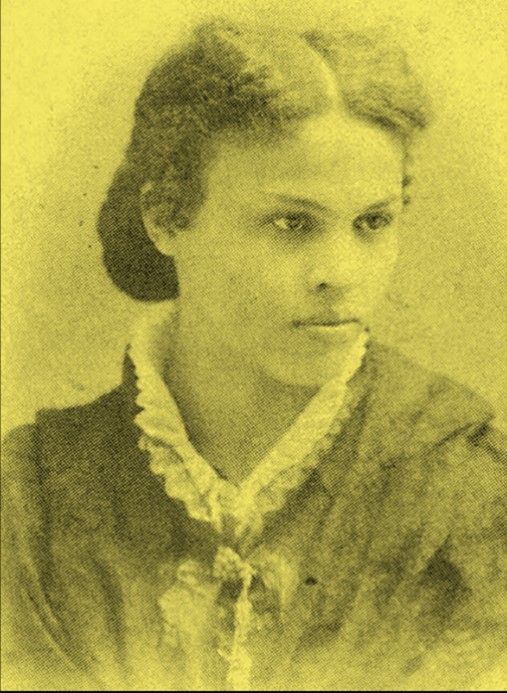

Sarah Loguen

One of Jermaine Loguen’s children, Sarah Loguen Fraser, was also a pioneer, but in the medical field. She was born in Syracuse on January 29, 1850, the fifth child of a family that would eventually include eight. Shortly after her father’s death, Sarah entered the Syracuse University College of Medicine. She graduated in 1876, becoming the fourth known African-American woman to become a doctor.

Loguen spent two years in Philadelphia and some time in Boston after graduation, but settled in Washington, D.C., in 1879, where she opened a medical practice. Three years later she married Charles Fraser in Syracuse and moved with him to the Dominican Republic. The couple settled in Santo Domingo, and Loguen was quickly licensed as a doctor in the country. This made her the first woman doctor in the Dominican Republic. Although she could only treat women and children, her practice was quickly successful, and the couple became both wealthy and well-respected. After her husband died, Loguen moved back to Washington in 1896. After a stint back in Syracuse (1901-1906) while her daughter attended Syracuse University, she returned to Washington for good in 1907, continuing to practice medicine. Loguen died over twenty years later on April 9, 1933.

After her death, flags in the Dominican Republic were flown at half-mast for nine days in mourning. More recently, SUNY Upstate Medical University created a scholarship in her memory, and the city of Syracuse named a street in her honor. The Dr. Sarah Loguen Medical Center was opened at the University in 2008.